VI. Execution

6.2. Liaison

Liaison with non-military actors is a primary core function. Liaison is needed to establish and to maintain two-way communication between the military force and non-military actors at the appropriate levels in order to facilitate interaction, harmonization, information sharing, integrated planning and conduct of operations/activities. Accordingly, CIMIC staff and forces will:

- Identify relevant actors as soon as possible,

- Develop a liaison structure,

- Organize and manage CIMIC Information,

- Maintain liaison with non-military actors within the force’s area of operations (AOO),

- Seek information to enhance SA and situational understanding (SU) in an open and transparent manner.

Key principles of CIMIC liaison are:

Single point of entry for liaison. Non-military actors tend to have a simply structured approach to areas of responsibility and grow quickly frustrated by repetitive approaches by different levels of the military for the same information. The creation of a liaison and co-ordination architecture minimizes duplication of effort by providing a clearly defined and accessible structure recognized by both the military and non-military actors alike.

Continuity. It takes time to cultivate and maximize liaison relationships between the military and non-military actors. Therefore a degree of continuity facilitates trust and understanding by both sides. The military need to know the organizational structure of the non-military actor, its planning and decision process and its motivation. The non-military actor needs to develop an understanding of how effective liaison with the military might benefit its civil aims/goals. The planning and tailoring of the liaison structure in line with changing circumstances demonstrates commitment and implies that the military attach importance to this principle.

Two-way flow of information. To be effective, military liaison to non-military actors must initiate and maintain a permanent exchange of information. It is important to be able to provide non-military actors an appropriate level of assessments of the military perspective to common areas of responsibility. This may comprise the form of an overview of the logistic pipeline issues, security situation, availability/usability of lines of communication (LOC), weather information or other mutual areas of responsibility. In each case, the information released must be current and relevant in order to be credible.

Liaison and coordination architecture

The CIMIC liaison and coordination architecture must be flexible and tailored to the mission and the situation. It must provide appropriate guidance to formations and units at all levels and have clear areas of responsibility. Key areas of CIMIC activity that specifically relate to liaison and co-ordination are highlighted below:

Direct liaison to key non-military actors. In any situation, certain non-military actors will be fundamental to achieve the mission because of their role or because of their capabilities. It is important to establish a good relationship to these key actors for a comprehensive approach to reach common goals. Usually each IO which is involved is a key actor. The most prominent IOs are:

- the United Nations (UN),

- the European Union (EU),

- the African Union (AU),

- the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and,

- the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Their missions are highly political by nature. See also chapter 3.

Keep in mind that the UN is involved in peacekeeping and political missions, thus quite often operate in similar theatres like NATO. The UN system comprises six principal organs, programs and funds, specialized independent agencies, departments and offices.

Pending on the situation it might be possible that even a small NGO has to be seen as a relevant non-military actor. Therefore, every non-military actor could be a key actor. This has to be taken into consideration while defining the key non-military actors

Direct liaison to host nation (HN). The support of the HN to military operations, at all levels, is essential, regarding de-confliction of activities, assistance where applicable and the provision of resources and material. It is also important to be familiar with HNs civil emergency plan (CEP) that in case of an emergency the military knows potential shortfalls, have an overview of possible limited resources and where the CEP might hamper own operations.

Credible liaison. To establish an effective liaison and coordination architecture it is necessary for the liaison assets to perform credibly.

Point of contact for civil community. The liaison and coordination architecture with their liaison assets, like liaison officers or CIMIC centres are important point of contacts for the civil community to get in touch with the military. This needs to be communicated to ensure that it gets known by the civilian community.

Competent advice to the right actor. The CIMIC liaison and coordination architecture needs to ensure that any advices or information for the civilian community are competent and reliable, and addresses the right actor on the right level. The most important tool to ensure that is the liaison matrix.

Liaison and co-ordination architecture matrix

In order to visualize the appropriate liaison and co-ordination architecture that needs to be established, a matrix showing liaison activity versus level of military command is strongly recommended. This architecture normally is laid down in the extended liaison matrix (ELM) as annex to the OPLAN. An example of a possible liaison and co-ordination architecture can be found in the annex. Prior to/during an operation a matrix should be constructed and completed to allow all levels of command to see what their liaison responsibilities are, and with whom. During an operation, if necessary, it might be required to be updated.

A tactical level HQ receives an ELM as annex to the OPLAN of the higher HQ. The tactical level HQ will need to translate the ELM into a format that depicts tactical level liaison responsibilities in detail. This translation ideally is prepared by the CIMIC staff at the respective level, while consulting both higher and subordinate HQs. The result is a cross-functional ELM tailored to the tactical level that will again be an annex to the respective level OPLAN.

A liaison and coordination matrix can be as simple or as complex as necessary to meet the requirement. The matrix needs to determine the key liaison responsibilities between the military and non-military actors, but could also be expanded to outline key CIMIC responsibilities to assist tactical teams, others than CIMIC, to visualize at what level, and by what means, they may meet the liaison responsibility.

CIMIC centre

CIMIC centres are a means to execute the CIMIC liaison and coordination architecture on the tactical level. CIMIC centres provide physical stationary location where the military force can interface with non-military actors. CIMIC centres enable the communication and cooperation between the civil community and the military. CIMIC centres must be assigned to an area of operations (AOO) permanently or only for a period of time connected to the operation in progress.

“Temporary” CIMIC centres could be fixed or mobile. The establishment of a mobile CIMIC centre has to be assessed, in particular in large AOOs.

Functions

The key functions of a CIMIC centre can be summarized as follows:

- Facilitation and coordination. The CIMIC centre:

- Provides a focal point for liaison with non-military actors in order to provide visibility and allow for harmonisation of military and civil activities within the AOO.

- Provides guidance on military support to civil actors and projects.

- Provides facilities for non-military actors such as meeting facilities, maps, and access to communications, security information etc. - Monitoring. The CIMIC centre plays a significant role in monitoring and tracking the civil situation. The use of a comprehensive reports and returns mechanism will enable this.

- Information management. The CIMIC centre facilitates sharing of information between non-military actors and Alliance forces through:

- Acting as a hub for exchanging information.

- Assisting situation monitoring by collecting and collating of information.

- Establishing an interface for situational information and assessments.

- Disseminating of information in support of information operations.

- Providing security information on curfews, mines, border status, routes and other threats.

The CIMIC centre as part of the CIMIC liaison architecture

The CIMIC centre is just one component that contributes to the overall force's CIMIC liaison architecture. It should not necessarily follow as an automatic assumption that there is a requirement to establish a CIMIC centre, the decision to do so should be based on an initial assessment. It must be closely coordinated with all other components such as the use of liaison officers and CIMIC meetings. Consideration needs to be given to the following:

- Requirement. The need for a CIMIC centre must be assessed. If there is no requirement, then the force should avoid establishing them. To ascertain the requirement the CIMIC staff should conduct an assessment asking questions such as:

- What is the operational requirement identified and specified in the operations plan (OPLAN Annex W)?

- How can liaison best be achieved/what is the best approach?

- Do the non-military actors already have a liaison network that the military can hook up to? Are these organizations willing to let the military participate in this network?

- If a CIMIC centre is required, what functions are to be performed? - Quantity. Identify the level of support and the amount of CIMIC centres required.

- Focal Points. For improving effectiveness of all actors in liaison and exchange of information, Alliance forces need to indicate and provide a single point of contact to the non-military actors. This does not mean that direct subject related interaction of certain branches of the Alliance forces with any non-military actor needs to be prevented. However, the single point of contact assumes the general interface from the military side and provides an entry point. The CIMIC centre assumes the role of a single point of contact, thus its staff needs to co-ordinate their activities with the CIMIC liaison officer dedicated to a particular non-military actor minimizing the amount of focal points and determining clear liaison responsibility.

- CIMIC centre allocation within an AOO. In order to determine the required number of CIMIC centres and their location the following factors need to be considered:

- Size of AOO.

- Population density.

- Availability of a common means of communication with non-military actors

- Organization, location and concentration of non-military actors. - Command and control. The command and control relationship between the CIMIC centre, the CIMIC unit providing the CIMIC centre and the headquarters they are assigned to, needs to be clearly defined to ensure consistency of approach.

- Coordination of activities. All CIMIC centres independent from the level they are assigned to should follow a consistent and coordinated approach to CIMIC activities and plans. Coordination between neighbouring CIMIC centres is also vital in order to avoid duplication of efforts and to provide similar information and facilities across the area.

- Service. A CIMIC centre needs to attract non-military actors and the local population to visit and exchange information and if possible co-ordinate mutual activities. The CIMIC centre therefore should provide services; these may include:

- Area security assessments (including unclassified military situation reports (SITREPS)).

- Mine awareness briefs/information/maps.

- Weather reports.

- Status of landlines of communication (LOC).

- Access to information technology (IT)/telecommunications facilities.

Establishing a CIMIC centre

Establishing a CIMIC centre, the following key factors need to be considered. A detailed checklist is attached in the annex (see Annex MM to the TTPs).

- Location. To be effective a CIMIC centre must be accessible for its target audience. The location will also be determined and often constrained by military operational requirements. The provision of security will often influence the decision for the location of a CIMIC centre and therefore restrain the effectiveness of a specific CIMIC centre. CIMIC centres must avoid being within the military perimeter of any barracks or HQ ("within the wire"), but the location must be determined carefully in order to enable access to all necessary military support.

- Manning. Since both military and civilian staff of the CIMIC centre will be responsible for varying functions these staff members need to be carefully selected. The requirements may differ considerably for each operation or CIMIC centre within the same AOO. An example for a manning list is attached in the annex.

- Communications. CIMIC centres must be equipped with adequate means of communications. This includes the ability to maintain a continuous contact between the CIMIC centre and the appropriate HQ as well as the ability to be able to communicate with all respective non-military actors.

- Accessibility. A CIMIC centre can only be effective in fulfilling all of its designated functions if it is accessible. If the respective non-military actors cannot gain access to, or if access is limited, the ability for civil-military liaison to take place will be severely hampered.

- Force protection. The requirement and level of force protection should be carefully tailored based on the threat assessment as conducted for each specific CIMIC centre. The level of force protection is directly influencing the accessibility of the CIMIC centre. The related HQ in its CIMIC centre force protection planning will consider scenarios as: evacuation, public disorder, terrorism and/or attacks.

- Information security. The threat to a CIMIC centre positioned in the civil community will need to be assessed continuously. The employment of civil staff, use of secure and insecure communications, access and general security of information will be laid down in the information security plan for the respective CIMIC centre.

- Infrastructure. Manning, Force Protection and information security requirements dictate the selection of suitable infrastructure. The best suitable infrastructure might be counterproductive to the nature of a CIMIC centre because non-military actors and the civil population might consider the chosen infrastructure as non-permissive.

- Funding. Costs relating to CIMIC centres might be significant and must be assessed during the planning stage. Expenses will not only relate to the number of centres but will also include construction costs, rent, amenities, communications costs, vehicles, administrative and staff costs (in particular that for civilian staff such as interpreters, etc).

- Life support. The ability for the force to sustain the CIMIC centre and its staff must also be considered during the planning process.

- Transport. The CIMIC centre must be provided with adequate transportation means and should have the possibility to locate these means in a safe and secure way.

- Method of Operation. The conduct of operation for a CIMIC centre will be laid down in the related HQ standing operating procedures (SOPs). Wherever possible these SOPs should be standardised across the entire AOO.

- Restrictions. The CIMIC centre must avoid restrictions based on language, gender, religion, local customs, cultural differences, etc as far as possible.

Keep in mind:

The CIMIC centre must ensure that it is not being seen as an integral part of the intelligence community. Information exchange must be carefully managed to ensure that trust is established and maintained.

Liaison Officer

The CIMIC liaison officers are to be found in the CIMIC branch and in other CIMIC units. Their main function is to serve as the single military point of contact for the civil environment in the scope of civil-military cooperation. The CIMIC liaison officer is his unit’s ambassador.

Basic activities and tasks of the CIMIC liaison officer

Based on the key principles of CIMIC liaison, the CIMIC liaison officer has to:

- liaise – either planned or ad hoc – identify counterparts, coordinate activities and support comprehensive planning and execution of the operation. The liaison officer has to use non-classified (communication) means within security constraints, restraints and precautions, in order to provide, receive and exchange information.

- be familiar with the counterparts’ mandate or mission. The liaison officer has to be prepared to work together with coalition partners in identifying unity of purpose whenever it is applicable with regard to specific non-military actors, mainly governmental and UN authorities.

- maintain close contact and build up a good working relationship with the relevant non-military actors. The relationship between CIMIC liaison officers and non-military actors must be based on mutual trust, confidence, respect and understanding. Take into consideration that:

- Some high level civil authorities (e.g. ministries, governors, embassies) might require a high-ranking, seasoned officer in order to be accepted;

- It is recommended to pay attention to the age of the liaison officer related to life and military experience, maturity and rank, before assigning him/her to the civil counterparts;

- Gender is to be taken into account. For example, it could be wise to deploy a female CIMIC liaison officer to achieve more effect, e.g. to local governmental institutions or offices where a woman is in charge. In addition many women work in different lOs and NGOs; therefore sending a female CIMIC liaison officer sometimes enables easier access; - maintain, expand and update a point of contact list.

- establish the first contact with all non-military actors, following the single point of contact principle. This rule has to be acknowledged and respected by all subject matter experts (SMEs) and headquarters branches. The CIMIC liaison officer is able to gain direct access to civil counterparts for other headquarters branches and SMEs (e.g. legal advisor (LEGAD), political advisor (POLAD), etc.)

- identify key capability gaps in the civil environment that might have impact on the mission. Based on the civil proposals and his own assessment he will recommend possible solutions to deal with these gaps and bring it to the attention of the appropriate branch(es) in the headquarters through the CIMIC branch.

- be aware of other liaison officer and CIMIC units’ activities, as directed in the Annex W of the OPLAN or operational order (OPORD). If a situation arises, where a conflict of interests is foreseeable, the CIMIC liaison officer has to seek de-confliction through the chain of command.

- promote commander’s intent and master messages according to StratCom. The CIMIC liaison officer has to propose and prepare visits of the commander related to the commander’s intent and interests.

Specific guidelines for liaison with non-military actors

- In order to control the CIMIC activities and to ensure the proper co-ordination and prioritization of tasks, the CIMIC liaison officers are tasked to improve the liaison activities with non-military actors.

- Non-military actors are experts within their respective fields conducting assessments of their own. Whereas the focus of these assessments may differ from that required by the military, it may nevertheless be of great value to review them and take them as a vital contribution to the military assessment process. Exchange of knowledge, experience, and information supports this process.

- Civil authorities have to be approached with respect, no matter how organized or effective they are. Patronizing them or giving them the feeling that we consider them to be of minor value could alienate them, which will in turn lead to less effective cooperation and may lead to information gaps.

- Taking security restrictions into account, the military has to share information with the relevant counterparts in order to improve civil-military relations.

- In order to liaise effectively with non-military actors CIMIC liaison officers have to be aware of their culture, identity, structures and procedures.

Similarities. Military actors have a lot in common with non-military actors: e.g. affiliation to their mission, commitment to peace and stability, a hard working attitude, international experience, life with hardship and danger, personal risk of injury, decision making under pressure, a certain degree of frustration with political decisions, et cetera.

Differences. Organizational goals, composition and structures of military and non-military actors are different. Many of the non-military actors work with a “code of conduct” based on the four basic humanitarian principles: impartiality, neutrality, humanity, and operational independence. Consequentially, the organizational goals of non-military actors see the alleviation of human suffering as their highest priority, and the use of armed forces as preparation for war and not as a real solution to any humanitarian problem. Soldiers and civilians use a different vocabulary. In order to understand each other, both sides should avoid using their specific terminology, at least in the beginning of the relationship.

Interpersonal Communication Skills for a meeting

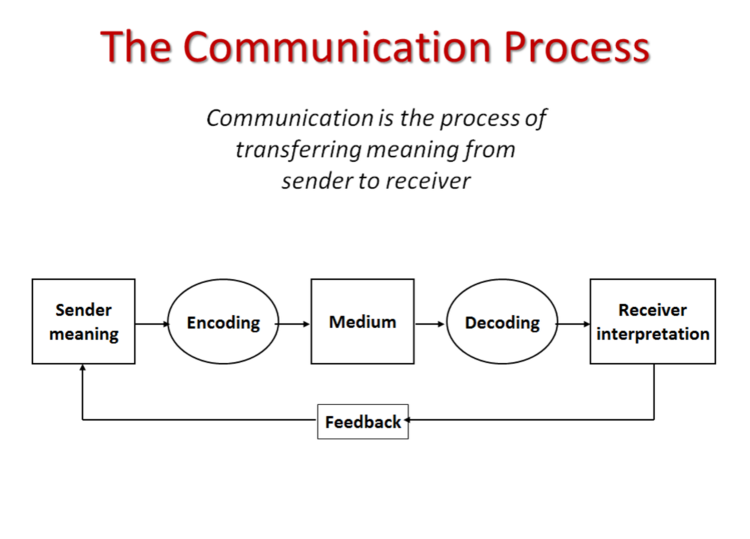

The Communication Process

- Encoding: The sender expresses a meaning in a message;

- Medium: the means that a sender uses to transmit the message;

- Decoding: the receiver gets the message;

- Interpretation: the receiver tries to understand the meaning of the message;

- Feedback: The receiver responds to the message.

Some terms to be explained:

- Cultural Noise: cultural variables that undermine the communication of intended meaning;

- Intercultural communication: when the member of one culture sends a message to a member of another culture;

- Attribution: the process in which people look for an explanation of another person’s behavior.

Context of communication

Context is the information that surrounds a communication and helps to convey the message

Low context society

- Message is explicit and the speaker tries to say precisely what is meant;

- Direct style: focus on speaker's statements;

- Silence may make people feel uncomfortable;

- Facial expressions and body language may be easy to interpret, if you understand the gestures of the speaker's culture;

- Meetings are often focused on objectives.

High context society

- Meetings with new contacts focus on relationships first. Business comes later;

- Indirect style: speaker does not spell out his message;

- Avoid saying "no";

- Avoid embarrassing people;

- Messages often are implicit: listener is expected to de-code verbal and non-verbal cues, such as voice, intonation, timing, body language;

- Silence is used to understand received messages and decide how to reply;

- If the culture is neutral (Asia), control body language and facial expressions – if you do not, people will not trust you or respect you.

Cultural Differences Affecting Communication

- Do not identify the counterpart’s home culture too quickly. Common cues (e.g., name, physical appearance, language, accent, location) may be unreliable;

- Counteract the tendency to formulate simple, consistent, stable images;

- Do not assume that all aspects of the culture are equally significant;

- Recognize that norms for interactions involving outsiders may differ from those for interactions between compatriots;Do not overestimate your familiarity with your counterpart’s culture.

Sensitive Issues

- The ideas of race, religion and nationality;

- The idea of dignity;

- Gender restrictions;

- Local living conditions;

- Local customs with regard to food, manners, etc.;

- Dress code or standards;

- The value that the local community attaches to life and health;

- Care of patients and handling the deceased;

- Differences in work ethics, values and perception;

- Consideration for other’s capabilities and operating practices;

- Use of gratuities to promote cooperation.

Intercultural Communication during CIMIC meetings

Before the meeting

- Know the history of the country, the conflict and the parties involved;

- Understand the personalities of the individuals you are about to deal with. Gather as much information as possible about recent meetings;

- Try to maximize knowledge of the subject matter and conduct background research;

- Always have a “mission statement” available that should contain an understandable explanation of your mission and what CIMIC is and what your tasks are;

- Review cultural items such as customs, traditions and local idioms and some phrases in the local language to minimize the chance of offending interviewees;

- In an ideal situation, CIMIC should be seen by non-military actors as a partner, not as an obstacle. Make sure that your verbal and non-verbal messages are consistent with the characteristics of a partnership;

- Prepare and ask questions that promote conversation and discuss them in advance, not only internally with the team, but also with the interpreter, so that he/she can advise on certain issues (culture, customs etc.);

- If possible, always make an appointment so your contact can prepare. Be aware of security aspects, sometimes making an appointment can harm your security and therefore an unannounced meeting is preferable;

- Consider a separate note-taker since the CIMIC officer who is leading the meeting should focus on the answers, non-verbal communication (facial expression, posture, appearance, voice tone, eye movement, etc.) of the counterpart;

- Arrange for interpreter support if needed.

- Set the appropriate atmosphere:

- Schedule the meeting at a mutually convenient time (be aware of security and culture);

- Allocate sufficient time (take in consideration cultural aspects of time);

- If possible, agree on a quiet location.

Conducting the meeting

- Relax and put your counterpart at ease;

- Take your gear off, if the situation permits it;

- Provide and/or accept refreshments if possible/if offered;

- Explain the purpose of your visit if it is not routine;

- Introduce your team, including your interpreter and explain everybody’s role (note-taker, observer, interpreter etc.);

- Start your conversation with small talk, be aware of local customs related to small talk;

- Try to build up a good personal relationship with your counterpart;

- Maintain and enhance control of the meeting by asking open-ended questions. They have the following advantages;

- Encourage others to disclose specific facts;

- Create a better atmosphere for the interview;

- Promote answers of more than a word or two;

- Allow others to relax;

- Increase your control;

- Do not confront your counterpart in a manner that challenges his/her integrity;

- Let your counterpart explain the meaning of unfamiliar terms. If necessary, let him/her spell out names to make sure you understand correctly;

- Do not interrupt in the middle of an answer. Be polite and attentive;

- Use your ‘active-listening’ skills (listening, reflecting and speaking);

- Do not be afraid of silence and do not rush into filling this silence with more questions.

- Suggest breaks to allow everybody to relax, especially your interpreter;

- Show appreciation and be prepared to answer questions asked by your counterpart, for he/she may also have a need for information;

- If your counterpart acts in an emotional way, you should show empathy before starting the factual meeting.

Ending the meeting

- Summarize what was said and, if possible, confirm it in writing.

- Agree on a time and place for a subsequent meeting.

- Exchange pleasantries and chit-chat in order to leave business and come back to a more personal level.

Considerations

- Acknowledge customs and greetings and show proper respect to dignities without acting timidly;

- Use local phrases appropriately;

- Know how to work with an interpreter;

- Never compromise own operations by inadvertently releasing critical information;

- Do not lie. If your lies catch up with you, you are done! Omit certain truths if necessary or tell the interviewee straight away that you are not entitled to answer certain questions;

- Do not make a promise you cannot keep. Otherwise you lose credibility.

After the meeting

- Actions after the meeting are as critical as gathering the information itself;

- Debrief your team, including the persons who waited outside the building or were observing the area;

- Write a meeting report and make sure your information is processed in the system;

- Coordinate with other branches as soon as possible, e.g. EOD, J2 etc. if unexpected issues demand an immediate response.