VI. Execution

6.1. General

The best planning is only successful if the planned tasks will be executed in the right way, and vice versa. That means CIMIC has to do the right things, at the right time, at the right place, with the right means to support the mission. This chapter will mainly focus on the “how to…” dynamic.

CIMIC activities

CIMIC’s contribution to achieve mission objectives is to support the desired effects in terms of the civil environment. These effects will be defined during the planning process (see 5.2.3). CIMIC related effects can be for example, an established relationship to non-military actors or a minimized negative impact of military actions on the civil environment. For creating such effects following CIMIC activities will be used:

- Communication. Effective cooperation is only possible if there is successful communication at all levels. This may prove difficult due to the absence of effective communications infrastructure. Based on the strategic level guidance the commander will be in contact with non-military actors. Keep in mind that sometimes local actors can have more power than the formal leaders. Equally, civil-military liaison officers are likely to be deployed to the non- military actors HQs. As described in section 6.2. it is important that CIMIC staff retain a proactive relationship with their counterparts in these organizations. Stable relationships enable CIMIC staff to explain military objectives/operation to non-military actors and gain in-depth knowledge of the role and responsibilities of the non-military actors. Additionally non-military actors are an essential source of information on various aspects of the civil environment (for example historical perspective, political structures, host nation capabilities and local culture).

Effective communication is an enabler for information sharing. Making information widely available to multiple responding civilian and military elements not only reduces duplication of effort, but also enhances coordination and collaboration and provides a common knowledge base so that critical information can be pooled, analyzed and validated. Civil- military collaboration networks need to be designed to facilitate sharing of information among non-military and military organizations. A collaborative information environment facilitates information sharing, while operations security measures will be considered at each step of the process.

Essential assets/ tasks for communication are as follows:

- Extended liaison matrix (ELM): The extended liaison matrix guides who communicates with whom on which level and when. (See annex)

- Cluster meetings: In AOOs where a humanitarian crisis is present the UN OCHA cluster system may be activated. Participating in cluster meetings or liaising to cluster leads fosters mutual exchange of information. (See Chapter 3)

- Effective communication infrastructure, like: Internet connection, telephone, meetings, boards, interpreters.

- Sustainability: In order to be effective it is important to communicate with all relevant military and non military actors within the AOO on regular base.

- Mutual communication: communication means information exchange. CIMIC liaison will only be respected as a valid partner when information is not only gathered but also own relevant information is shared with non-military actors (See chapter 6.1.2).

- Communicate with respect: A mutual respectful treatment not only refers to one's own behavior but implies a respectful behavior of the counterpart. - Planning. It is critical that CIMIC staff are represented in the commander’s planning groups. Factors relating to the civil environment are likely to impact upon all aspects of operations and related staff work. Therefore, the CIMIC staff should work in close cooperation with all military staff branches, and be part of all cross headquarters processes and bodies, to ensure that civil-related factors are fully integrated into all operation plans. To be effective, CIMIC staff must be included on ground reconnaissance missions and should maintain close contact with relevant civil organizations and government officials in the run-up to an operation. Whenever possible CIMIC staff should participate in civilian planning and assessment groups. CIMIC support covers the political mandate, governance, non-military actors and the civilian population and results in the CIMIC contribution to the comprehensive preparation of the operational environment. At the same time CIMIC assets provide information, requests and assessments for the staff. Details of the CIMIC contribution to planning are laid down in the CIMIC Functional Planning Guide.

(See Chapter 5.2)

- Coordination. Different mandates, cultures and perspectives require coordination of activities between the military and non-military actors to ensure that objectives are not compromised. Internal coordination is needed with all staff branches and functions to mutually increase the effectiveness and efficiency of their respective actions.

Essential assets/ tasks for coordination are as follow:

- Meeting: A meeting is the most effective tool to coordinate joint efforts.

- Coordination and harmonization: The military does not coordinate the tasks of non-military actors, but need to harmonize the joint efforts.

- UNOCHA: Takes the lead in coordinating humanitarian action, although in response to specific disasters specialized agencies may take on this role. Keep in mind that UNOCHA coordinates effective and principled humanitarian action in partnership with national and international actors. It coordinates also global humanitarian funding appeals and manages global and country-specific humanitarian response funds. - Facilitating civil-military interaction. CIMIC interacts with non-military actors and thereby enables and facilitates CMI for other headquarters staff. CIMIC personnel are trained in bringing together the appropriate military and non-military actors. Facilitating CMI will differ at each level of command due to the focus, responsibilities and scope of coordination.

Essential assets/ tasks for facilitating CMI are as follows:

- Non-military actors: It is important to have a complete overview about the aims, capabilities and characteristics of non-military actors within the AOO.

- CIMIC principles: For a successful facilitating of CMI it is vital to conform to the CIMIC principles

(See Chapter 2.1). - Assessments. CIMIC personnel will be involved in a variety of assessments. These assessments are to examine particular geographic areas, occasions, groups, actors or subjects of special interest, etc.. CIMIC assessments contribute to the situational awareness and understanding of the staff and inform the planning and decision making process. CIMIC also contributes to Operations Assessment in order to generate an understanding of the mission’s progress and success. (See Chapter 5.3)

Information sharing

Information sharing is the exchange of information between at least two actors. CIMIC exchanges information inside the military and with non-military actors, for the mutual use of information.

For the military it is vital to share information with non-military actors to reach common goals and objectives. Trust and mutual understanding are prerequisites to information exchange within the CIMIC community.

Making information widely available enhances coordination and collaboration and provides a common knowledge base so that critical information can be pooled, analysed and validated. Information sharing is a tool to prevent duplications, to increase the effectiveness and to save resources.

Information Sharing is a dynamic setting that ranges from interpersonal (face-to-face), to interorganizational, to high-tech systems (machine-to-machine) and is largely based on:

Willingness to share - revolves around a cultural openness to pursue relationships based on respect, trust and common goals.

Factors:

Culture: Cultivate a mindset for information sharing. All personnel involved in civilian-military cooperation, including the leadership, ought to recognize information sharing as a vital resource.

Trust: generate a steady flow of truth-telling between military and civilian organizations by letting know yourself, your intentions and limitations, being honest, open to feedback, and accept the civilian organizations as a separate entity by cultivating a culture of transparency.

Training and education: Ensure actors are aware of the advantages of information sharing.

Ability to share - is dependent on the established organizational policies, procedures and capabilities of those involved.

Factors:

Classification and releasability: The ability to share information is limited by the information’s classification level, and the authority of potential viewing parties.

Training and education: Actors must know with whom they ought to share information, and how to do so.

Infrastructure: There are usually bureaucratic barriers in place, designed to protect information. However, information sharing infrastructure can also help lubricate the flow of information.

Asymmetry of capabilities: harmonize the efforts among the organizations towards a similar objective in order to achieve collaboration.

Essential assets/ tasks for information sharing:

- Identify participants: clearly identify the main actors and their role in a project, task, or event.

- Built institutional trust: it should be set through the institutionalization of Memoranda of Understanding or, as a last resource, by finding other solutions to Information-Sharing Barriers (conferences, workshops, briefings, etc). Additionally, special relationships should be established with key political, social, and military actors even if they are geographically divided.

- Cultivate interpersonal relationships: they are the pillars of trust, commitment, as well as, transparency when exchanging information.

- Support a common understanding: based on the use of standard protocols, common language and shared analysis.

- Classification as low as possible: when processing information the lowest classification possible should be used. This enhances the information accessibility by allowing relevant information to be provided to non-military actors. In case of classified information, there is the option to release information based on its age. Evaluate the information to determine if the classification can be downgraded.

- Use of humanitarian Information services and platforms: it allows a greater reach in information sharing as it should be the most practical solution with non-military actors. The humanitarian community offer several technological information sharing platforms and services. Military forces can join the following unclassified/open Web-based platforms to share information with the various organizations in the field, contributing for a quicker communication:

Platform / Service | Aim | |

| Making data easy to find and use for analysis | |

| Self-managed contact management tool https://humanitarian.id/ | |

| leading online source for reliable and timely humanitarian information on global crises and disasters | |

| place where the disaster response community can share, find, and collaborate on information to inform strategic decisions. | |

| global, open-source risk assessment for humanitarian crises and disasters. | |

| suite of tools for field data collection for use in challenging environments https://www.kobotoolbox.org/ | |

| enable crisis responders to better understand how to address the world's disasters |

- Training and education: personnel involved in information sharing should have an understanding of the humanitarian principles and International Humanitarian Law (IHL), Human Rights Law (HRL) to further simplify civil–military dialogue so that misunderstandings in roles, aims, tasks and perceptions can be better managed.

CIMIC and media

Strategic communications (StratCom) effort aims to enhance coherence of all information and communication activities and capabilities, both civilian and military. Therefore it is necessary for CIMIC to know, how to deal with media.

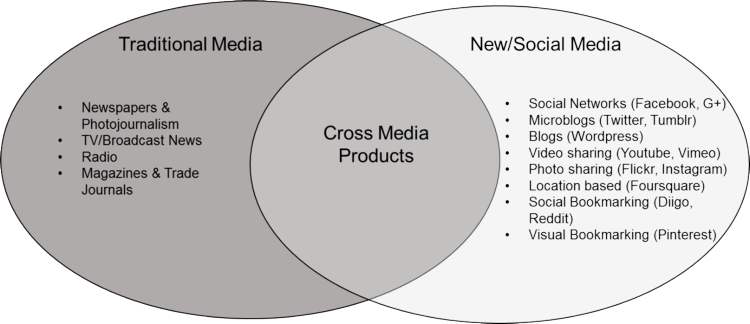

Types of media.

CIMIC also supports the force by communicating accurate information in a timely manner to non-military actors. Transparent communication improves public awareness and understanding of the military aspects of the Alliance’s role, aims, and activities, thereby enhancing organizational credibility and legimitacy.

If CIMIC teams face journalists (including cameras or microphones) they should be able to react, to decide, to state or to solve the situation by following the overall regulations with key messages and own experiences.

Therefore it is quite vital to understand the interviewer’s position, his way and motivation for getting a “good” or fitting statement. To handle such kind of situations by sending out your personal point of view in combination with the delivered mission defined key messages it is important to know the Do´s and Don’t´s regarding how to deal with media.

It might also be a solution to involve the public affairs office (PAO) by giving the contact data of PAO to the media, especially if the CIMIC team assumes possible challenges or if the journalist creates high pressure.

A positive report about the mission and/or the CIMIC work is important and supports directly the commander and the whole mission. In general media products (positive or negative) will give an immediate feedback and have an impact on the attitude of all actors toward the mission.

Media products will be seen and analyzed by J2 and the PAO and be reported to the commander. So it is important to increase positive feelings/sentiments for the mission which can strengthen existing relationships/partnerships and/or build up new relationships/partnerships with non-military actors.

Using the media for spreading our defined key-messages is a supporting factor for the whole mission. Overall NATO guidelines are:

- Tell and show the NATO story.

- Provide accurate information in a timely manner.

- Ensure that information provided is consistent, complementary, and coordinated.

- Practice appropriate operational security.

- Conduct work mindful of multinational sensitivities, and respectful of the local and regional cultural environment.

- Stick to unclassified facts, avoid

-Operational programs

-Deployment details

-Capability shortfalls

-Casualty details

-Morale

-Mission-specific information

In addition the following characteristics need also to be taken into account when interacting with media:

- Authenticity: Being authentic and direct as in interpersonal communication. Always reply (positive and negative comments).Thank the journalist for contacting you.

- Transparency: Trust building.

- Decentralization: Nobody is the centre of universe (not alone to give answers; there are maybe other SMEs which can answer topic related questions.)

- Speed: Social Media are fast and can create fast products world-wide (real-time).

- Collaborate: This will increase visibility and strengthen partnerships for further actions.

- Structure: Always engage with a clear head. Think before talking /publishing; take your time. Treat everything published online as being available to everyone. Controlling the full message is impossible.

Do’s and Don’ts:

- Avoid military terminology and technicalities (if possible).

- Limit the use of acronyms (or explain them).

- Never show arrogance or superiority.

- Recognize and correct your mistakes.

- If you don’t know an answer, provide a solution (other SME,...).

- Don’t respond to malicious behavior or threats – report it.

- Never lie.

- Be aware of what you say. It can be online immediately.

- Think like your opponent and focus on his interests.

- If asked by the media for a response: Provide rapid response (in accordance with your duty). Provide a timing if answer requires time to be produced.

- Use Key Messages and talking points (STRATCOM messages = official version) in order to send the same message every time when dealing with media.

- Always speak personally, unless officially authorized.

- Stay away from policy or speculation.

Checklists regarding dealing with media can be found in the annex.

Working with Interpreters

Most military operations are conducted in countries where CIMIC personnel lack the linguistic ability to communicate effectively with the local population. Working with interpreters is often the best or only option, but must be considered a less satisfactory substitute for direct communication. Be aware that a conversation conducted through an interpreter goes more slowly than a normal conversation. Plan your time accordingly.

For the use within military operations we can distinguish between 2 types of interpreters; the professional interpreter (often from your own country and culture which can also be military personnel trained in the language of the mission area) and the locally hired interpreter (LHI). When employing a LHI take in consideration where the LHI comes from or still lives. Employing a LHI who comes from a different region of the country limits his/her bias towards the persons he/she will meet. Also it increases the level of security for the LHI. For example in some cases families of LHI have been threatened because the LHI works for the military force.

In some mission areas it could be culturally sensitive for men to talk to women. Therefore it could be more effective to use female interpreters. This is something to take in consideration during the planning of a mission.

Your interpreter is an important member of your team and is essential for the success of your CIMIC tasks. Make sure you and your team acts accordingly.

Basic guidelines on the use of interpreters

- Speak with the interpreter beforehand about the subject of the conversation (depends on the level of OPSEC), how you would like the conversation to develop, and what the aims are.

- Inform the interpreter in advance that the translation has to be done consecutively, e.g. there will be a pause for the interpreter to provide the translation after every 2 or 3 sentences (depending on the complexity of the subject, the listener’s comprehension level and the interpreter’s skills). Simultaneous interpretation – in which an interpreter translates a speaker’s words at the same time as they are spoken – places far greater demands on the interpreter. Prior to the actual conversation it is advisable to conduct a try-out with your (new) interpreter;

- Check in advance whether any sensitivity (as a result of ethnic background, position of power, gender, etc.) may exist between the interpreter and the person you are speaking with. Make sure that the interpreter always behaves objectively and in a neutral manner towards the other person;

- If you are going to give a speech or a presentation, provide your interpreter beforehand with the full text, or at least the main points of what you are going to say. If the subject is of a specialized (military) nature, then give the interpreter topic-related advice for preparation. Provide the interpreter with a list of frequently used specialist terms and terminology, as well as with copies of charts, images and diagrams that are going to be used during the presentation;

- Agree in advance where the interpreter will sit. If you are standing to conduct the conversation, your interpreter should also stand. A good interpreter is an extension of the speaker – that is why you must always make sure the interpreter is clearly audible and visible to the listener(s);

- Inexperienced interpreters and people who have received no training as professional interpreters can feel ashamed if they have not heard or understood something properly, and they are afraid to ask you to repeat what you said. Emphasize to the interpreter to ask you to repeat if necessary, because this is always better than providing a quick but inaccurate (or even incorrect) translation;

- If more interpreters are present during the conversation agree on who will be translating which part of the meeting and for whom. If multiple interpreters will translate for different people attending the meeting this can create confusion;

When communicating through your interpreter.

- At the start of the conversation, do not forget to introduce the interpreter to the other people taking part, so that everyone knows who the interpreter is and why he/she is present. Then explain to the attendees how you will conduct the conversation through the interpreter. What is self-evident to some people may cause confusion to others who have possibly never communicated through an interpreter or heard a foreign language. Ask your counterparts to speak slowly with pauses after every 2 or 3 sentences to allow your interpreter to translate;

- Observe the non-verbal communication of your counterpart when your message is interpreted by the interpreter and keep eye contact;

- It is important to speak slowly so that the interpreter can consecutively interpret and make notes if needed;

- If necessary, modify your use of language by choosing widely used, understandable terms whenever possible, and by avoiding (military) jargon and abbreviations;

- Make sure the interpreter is always close to you when you are speaking, so that the listeners do not have to keep switching their attention between you and your interpreter. The interpreter should preferably also be able to see you in order to observe your body language;

- An interpreter has to provide a literal and truthful translation of everything that is said by the participants in the conversation. In practice this is less straightforward than it seems. An interpreter is only permitted to merely provide a brief summary if you have explicitly requested him or her to do so;

- During long conversations, provide breaks more often than usual. Taking in information received through an interpreter is more difficult than during a normal conversation;

- If an interpreter behaves assertively, prevent him/her from taking the initiative away from you during the conversation;

After the communication through an interpreter.

- Evaluate the communication and performance of the interpreter and your own performance;

- Ask the interpreter about the impression of the counterpart and if applicable how you can develop your relationship with the counterpart;

- Evaluate the content of the communication. Go over your own notes and the notes of the interpreter. Make sure you capture all important information you have received.