VI. Execution

6.4. CIMIC staff and field elements

Cooperation within the Staff/HQ

A sound cultural understanding of the overall cultural context in which you operate will allow you to complete these tasks with more confidence. Understanding the cultural orientation and dynamics of the population in the AOO is of significance for the achievement of the objective. To this purpose, not only the CIMIC staff but all the HQ should know the sensitivities of the population. To achieve this, a working group led by J/X 9 and supported by all the relevant staff at the HQ can be formed and the group can create a product which clearly pictures the social fabrics of the population and regularly inform all the personnel (especially those who are in close and constant interaction with non-military actors) about the civilian population and their sensitivities. Any changes in the attitudes of the population should be monitored closely and the personnel should be updated.

It is extremely important that the J/X 9 branch is involved in the operations planning process (OPP) and is in constant dialogue with the other branches in order to avoid redundancies. In order to mitigate the impact and maximize the effect, close liaison between/among all branches involved in the civil environment will be necessary. CIMIC staff should also know the clusters and cluster leads and which branch/branches of the HQ staff should be in constant coordination with the relevant cluster. It is important that CIMIC staff remain the focal point for civil-military matters. The commander has to have a clear civil picture on which to base decision making.

This table suggests possible two-way links that should be considered between branches and the CIMIC focus:

BRANCH | IMIC COORDINATION LINKAGES |

Legal advisor |

|

Political advisor |

|

Gender advisor |

|

Cultural advisor |

|

Personnel |

|

Intelligence |

|

Current Operations |

|

Planning |

|

Operations, support, targeting and battle damage assessment |

|

Information Operations, Psychological Operations and Public Affairs |

|

Military engineering |

|

Military geographics |

|

Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) |

|

Logistics |

|

Medical support / environmental health |

|

Communications and information systems (CIS) |

|

Training |

|

Budget and finance |

|

Military police (MP) |

|

Maritime |

|

Air |

|

Key leader engagement |

|

StratCom |

|

CIMIC contribution to HQ R2/CCIR

CIMIC, as a part of R2 system, is required in every HQ to contribute to the system in accordance with the overall reporting architecture. CIMIC input to commander’s critical information requirement (CCIR) will vary on a mission. In some cases CCIR’s provided by J/X 9 may be crucial for the success of the operation.

CIMIC contribution to de-confliction of civilian mass movements

Civilian mass movements can hamper freedom of movement and freedom of manouevre of military operations. On the other hand military operations can endanger civilian populace be it local population, refugees or internally displaced persons (IDPs). It is therefore in the commander’s interest to de-conflict civilian mass movements with military operations.

CIMIC is to contribute by providing an up to date civilian situation showing current IDP and refugee camps, current and expected mass movements of IDPs and refugees IOT support J/X 4 movement and J/X 3/5 operations planning.

The responsibility for safety and security of the civilian local population as well as IDPs and refugees lies with the host nation authorities. Host nation bear the primary responsibility for a safe and secure environment (SASE) for local, IDP and refugee communities / camps. Local authorities are responsible to provide basic needs. Where host nation authorities lack ability or commitment to provide basic needs of the respective communities UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) and IOM (International Organisation for Migration) are mandated and in lead within the UN OCHA cluster system (UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs) – main clusters are the camp coordination and camp management cluster (CCCM – UNHCR and IOM in lead), the emergency shelter cluster (UNHCR and IFRC – International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies in lead) and protection cluster (UNHCR in lead). Other IO and NGO working in this field are usually coordinating their activities within the UN OCHA cluster system.

Civilian mass movements can often not be directly steered and controlled. Deconfliction can happen by traffic control measures of host nation and NATO military police. Civilian mass movements can be influenced by CIMIC liaison and information operations which should primarily be communicated via host nation authorities and the respective humanitarian organisations within the OCHA cluster system.

Where host nation authorities and humanitarian organisations are not able or willing to fully provide SASE and basic needs for IDP and refugee communities, NATO military may have to support with providing SASE and contributions to humanitarian assistance. Military support is here only applicable as a last resort in accordance with the IASC Guidelines on the Use of Military and Civil Defence Assets to Support United Nations Humanitarian Activities in Complex Emergencies.

Host Nation Support

Host-nation support (HNS) seeks to provide the commander and the troop contributing nations with support in the form of materiel, facilities and services and includes area security and administrative support in accordance with negotiated arrangements between the sending nations and/or NATO and the host government. As such, HNS facilitates the introduction of forces into the joint operations area by providing essential reception, staging and onward movement support. HNS may also reduce the amount of logistic forces and materiel required to sustain and re-deploy forces that would otherwise have to have been provided by sending nations.

Cooperation and coordination in the provision and use of HNS is essential. The aim is not simply to eliminate competition for scarce resources, but also to optimize the support that the HN may make available in order to facilitate mission accomplishment. It must be carried out at appropriate levels and may include non-NATO nations as well as non-military actors which may operate with or alongside NATO.

J/X 4 will lead HNS planning and the development of host-nation support arrangements (HNSA) in close cooperation with legal, financial (J8), civil military cooperation (CIMIC) (J/X 9) and other relevant staff functions both internally and within the HN and the sending nations. CIMIC complements the efforts of J4 staff in establishing HNS and may be directly involved in the drafting and negotiating of HNSA.

CIMIC may also offer support to J/X 4 in the following areas:

- Participation in the fact finding visits that CIMIC staff may conduct within the target country for data gathering, initial assessments and establishment of liaison and coordination mechanisms;

- Information on the overall status and capability of the HN's economy, infrastructure, health care and lines of communications to support the operational logistic requirements;

- Access to appropriate HN authorities with whom negotiations will need to be conducted and at the regional and local levels with whom the execution of HNS will need to be coordinated;

- Advice on other established arrangements (sending nations, IOs, governmental organizations and/or NGOs) that may compete or conflict with the proposed HNS arrangements.

- Assistance with the negotiation of HNSA by providing inputs on the HN’s governmental structures and support capabilities;

Due to their contacts and network, CIMIC personnel contribute to the military planning on the use of HNS by assessing the implications of military involvement on the local economy and help establish interaction with non-military actors in cases where de-confliction and harmonization between military and civil needs are required. CIMIC staff can also assist with arranging access to local civil resources and ensure that such access does not compromise the needs of the local population or other non-military actors involved. Civil-military interaction within HNS, should always be managed in full consultation with the appropriate military and non-military authorities of the host nation.

NATO Force Integration Units. As part of NATO’s adaptation to security challenges from the east and the south, the Alliance has established eight NATO Force Integration Units (NFIU). These NFIUs are small headquarters including CIMIC personnel at the tactical level, which will help facilitate the rapid deployment of Allied forces to the Eastern part of the Alliance, support collective defense planning and assist in coordinating training and exercises. They will also work with host nations to identify logistical networks, transportation routes and supporting infrastructure to ensure that NATO’s high-readiness forces can deploy to the region as quickly as possible and work together effectively.

Host nation support – core functions in support to the maritime environment

Civil and military assistance rendered in peace, crisis or war by a host nation to NATO and/or other forces and NATO organizations which are located on, operating on/from, or in transit through the host nation’s territory (AAP-6, Allied Glossary of Terms and Definitions).

HNS can involve the following entities or support:

- Government agencies:

police, fire-fighters, translators/liaison personnel, customs and immigration; - HN civilians:

labour pool; - HN military units:

navy, army, air force, coast guard, military police, border guard; - HN facilities:

harbour entrance control towers, boathouses; checkpoints or guard posts; - Civilian contractors:

support services i.e. bunkering, shipyard and repair; - Designated roles:

rail operations, air traffic control, maritime coordination centre, search and rescue, harbour pilot services, firefighters and medical facilities and teams; - Intelligence support:

devices, facilities and intelligence products; - Logistic support:

supplies, equipment and staging areas.

These core functions are assessed to be vital to and will as such need to be performed by NATO, in the event that the HN is incapable of providing a satisfactory level of support:

- Safety;

- Security;

- Harbour management and infrastructure;

- Logistics.

HN safety:

Pilot service, harbour management and vessel traffic service are all vital stakeholders regarding upholding the safety of navigation in the harbour, entrances and adjacent holding or anchorage areas. Close Liaison with these stakeholders will ensure that a collective effort is established to minimize disruptions to the routine operation of harbour areas.

HN security:

Host nation military forces will be unique to their particular culture and location. This includes their quantity, quality and effectiveness. Regardless of their situation or status at the outset of operations, HN forces will be indispensable in terms of the execution of stabilization and, more importantly, creating enduring solutions. Professional HN military forces will be invaluable for intelligence and understanding the operating environment; they may even have a harbor protection capability or elements of it (e.g. infrastructures, patrol boats, land patrol and other). If NATO elements are working with HN military forces, care must be taken to ensure that the population perceives their nation’s security forces as capable, competent and professional. Failure to do so will generally undermine the HN government’s legitimacy.

HN law enforcement forces play a valuable role in stabilization if these forces are competent and trustworthy. If they are legitimate in the eyes of the population, they are likely to have access to detailed intelligence on adversary leaders, networks and links to criminal or terrorist elements. The presence of local law enforcement, particularly if they are perceived to be leading activities, will have a stabilizing and normalizing impact on the population.

HN Harbour international ship and port security (ISPS)/Security Implementation. If present, international ship and port security code will have a positive contribution to the overall security, since established physical restrictions, surveillance and access control can be utilized in the overall harbor security.

HN harbour management and infrastructure:

One of the most important local authorities is the harbour master. The coordination with this authority should be planned in advance in order to integrate his information within the CIMIC structure. Liaison or daily meetings, where planned activities from both sides are exchanged, should be arranged. The information-exchange with the harbour master is of high importance for the coordination. CIMIC can provide the harbour master additional threat information from NATO channels, which will help the harbour master to adapt the ISPS-measures and increase the security of the harbour.

HN logistic support:

HNS plays an important role not only for the HPO itself but as well to guarantee its survivability. The HN level of cooperation and capability will influence the design in all planning. HNS is normally based on agreements that commit the HN to provide specific support under prescribed conditions.

In general, HNS is highly situational and heavily dependent upon the operational capabilities of the HN and its political acceptance. Maximum use of HN capabilities is especially critical when NATO forces may not be in place or have outpaced their logistics support. The amount of civil or military support provided by HN will depend on its national laws, industrial capability, and willingness to give such support.

Project management

A CIMIC is a specific task undertaken by the military force either in isolation or in partnership with one or more non-military actors. Conducting CIMIC projects in isolation can only be the exception in an environment where non-military actors are not able to operate. In all other scenarios, a partnership is essential and will enhance the feasibility and sustainability of a project (local ownership). Normally, the government or non-military actors are responsible for the provision of basic needs and services.

Every project needs to be in line with the HN’s development plan and initiatives of the international community. In the absence of a functioning government and state authorities, envisioned CIMIC projects need to be even stronger analyzed concerning their relevance and effects.

Projects are not a core activity of CIMIC, but if a commander decides to carry out projects (just as a tool … ) , CIMIC should always be involved from the very beginning of the planning process. A commander should deny any project implementation which has not been assessed by the CIMIC branch and which has not been approved by the responsible local officials/ministries.

When properly planned and executed, projects can benefit the overall mission, can serve as a significant contribution to force protection and will improve the situation of the non-military actors and their environment. It is not the amount of money which makes a project successful but the consideration of the factors mentioned above. A poorly-planned and implemented project (e.g. poor sustainability) will, in turn, only benefit the contractor and damage the reputation of the military. When it comes to projects, less is sometimes more.

Project characteristics

If the task is to establish a CIMIC project, following characteristics must be taken into consideration:

Size and complexity: Projects will vary in size and complexity. Whilst this will be mission dependent, projects may be of greater significance in crisis response operations than in collective defense scenarios.

Coordination: Coordination is a critical factor in the project management process. CIMIC should aim to conduct CIMIC project focus at the appropriate level in order to coordinate, monitor and track projects within the AOO. The grouping of projects into categories such as health, education etc. may be used in order to assist coordination, as this is also in line with e.g. the UN cluster approach.

Mission oriented: Projects have to be in support of the mission. This may not always be in line with the aims of some or all of the non-military actors involved into the project.

Clearly defined: The purpose, scope and parameters of a project must be clearly identified and defined before its development and initiation.

Monitored: In order to provide full visibility of ongoing projects CIMIC staff has to track and report on the progress. This can be achieved by including that into the CIMIC report and return system. Simultaneously it gives the opportunity to check if the project is still developing into the right direction to reach the expected objectives.

Feasibility: A feasibility study must be conducted before the acceptance of any project in order to ensure that a project is not only achievable, but also that the beneficiary is enabled to maintain the usage. The consequences of being unable to finalize a project may will result in a negative impact upon the force.

Level: CIMIC projects can be conducted at all levels, but are mainly conducted at the tactical level. In particular cases, the operational level might involve itself for setting guidelines, ensuring a consistent approach and a well-balanced engagement across the joint operations area. When conducted at the tactical level it is important that subordinate units do not work in isolation and that the direction given by the higher headquarters is followed. This is not only in order to ensure coordination but also to encourage consistency across the area of operations (AOO) and unity of effort. A well-balanced CIMIC effort across the AOO will also be more likely to portray a favorable military image in relation to the non-military actors.

Commitment: Wherever possible, military participation and involvement must be kept to a minimum. The aim should be to encourage the hand-over of projects to the non-military actors at the earliest practical opportunity. Military resources and efforts, when involved, should balance the short term gains against long-term effects of their projects, regarding self-sustainment and capacity building. The duration of the mission against the required time for conducting the project is a further consideration to be made. Justifying projects with “force acceptance” or “force protection” might also be a rationale for focusing on a quick impact.

Impartiality: Whenever conducting projects the aim should be to be as impartial as possible regarding non-military actors and the civil environment.

Funding: The NATO funding system rarely includes funds for CIMIC projects. As such, it is essential that funding sources, including donor organizations, nations and certain deployed units are identified as early as possible (phase 0). A system for the disbursement of funds with agreed procedures and tracking systems must be in place before any agreement to sponsor a project is undertaken. CIMIC planners have to be aware of the fact that “3rd party” funding will lead to a difficult focus (project-wise), a different project control and ultimately might result in other than planned (sometimes even undesired) effects. Utilizing of military capacities (like military engineers or military medical elements) within available resources for conducting projects can increase the effectiveness of the given budget.

Cultural awareness: Projects need to be in line and must reflect respect with the cultural background of the respective society. A mismatch on this could have a negative impact for the overall mission and most likely results in limited acceptance and utilization.

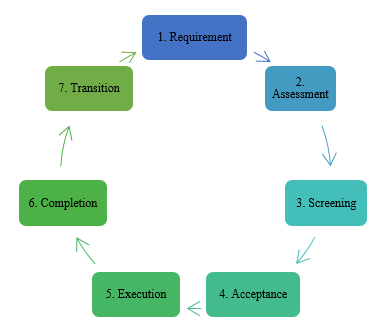

Project approach

- Requirement: Ensure the project is .

- Assessment: Ensure the project is in support of the commander’s mission.

- Screening: Ensure there is a need and no duplication of effort.

- Acceptance: Ensure local .

- Execution: Ensure local .

- Completion: Ensure there are no additional hidden commitments and the project will be maintained and sustained.

- Transition: Make sure the project is handed over in full and sustainable local responsibility.

Do no harm

During the planning process of a project, it might be helpful to ask the same do no harm questions in order to avoid possible sources of problems.

Impacts on other communities

- How is the relationship between the people we are assisting and their neighbors?

- Will our assistance make those relations better or worse or will there be no effect at all?

- Have you considered the needs/preferences/priorities of neighboring communities?

- Have you considered the potential or actual negative effects on other communities?

Effects on perceptions and relations

- Will men, women, boys, girls and other vulnerable groups like older people or persons with disabilities benefit equally from the project? (include a gender perspective).

- Is anyone already doing something similar here, or nearby?

- Have you considered sources of harmful competition, suspicion, jealousy or biases within and between the communities in the area where you are working?

- Will this activity avoid or foster harmful competition, suspicion, jealousy or biases? Who profits from this project? Can it be misused or not used at all?

- Are the resources we are providing at any risk from theft, diversion, corruption or other unwanted use?

Quick Impact Projects in UN missions

UN mission quick impact projects (QIP) are funded from peacekeeping budget, and are intended to provide a flexible disbursement facility to support, at short notice, local level, non-recurrent activities in the areas of health, education, public infrastructure and social services, that are designed to promote and facilitate the UN peace support effort in the given country.

In some UN missions, CIMIC officers are responsible for managing some of the QIPs, whilst in others CIMIC officers will work closely with civil affairs or humanitarian affairs officers to implement these projects. It is thus important that CIMIC officers understand what QIPs are, and how they work.

Military contingents are encouraged to identify potential projects in their AOO, in close consultation with beneficiaries, community leaders and their civil affairs and/or humanitarian affairs colleagues. Any mission component or section, (e.g. military units, military observers, CIVPOL, political affairs, civil affairs, human rights, public information, humanitarian affairs, DDR, or electoral affairs) may identify and propose QIPs, and such proposals should ideally be the result of a multi-functional team effort. Once such a project has been identified, a project proposal should be prepared and submitted for approval. In most UN missions, QIPs are managed by the humanitarian affairs section or the civil affairs section on behalf of the SRSG. In some case CIMIC officers may be involved in assisting with the identification, facilitation and monitoring of QIPs.

QIPs can contribute to building confidence in the mission, mandate and/or peace process in a number of ways, including:

- Through the type of project implemented, for example one that rapidly addresses key community needs, which can demonstrate early peace dividends and/or increase confidents in the mission;

- By cementing or supporting conflict management or resolutions activities;

- By building legitimacy and capacity of local authorities or organizations;

- Through the dialogue and interaction that comes with the process of project identification, stakeholder consultation and project implementation;

- By “opening doors” and establishing communication channels between the mission and host community;

- By helping uniformed components (UN military or police) to engage with local communities through involvement in project development, monitoring and/or implementation. This can include using military engineering assets to support a project or direct implementation by the military.

Throughout the project cycle, it is essential to be guided by the overarching principles of local ownership, gender, culture and context sensitivity. Good project and programme management are also essential to building confidence through QIPs. Bad project management, including in the selection, implementation and monitoring of QIPs, can undermine confidence and may compound conflict. Bad practice in QIP management might include:

- Falling to properly consult with stakeholders, which can lead to a lack of buy-in or a failure to address real needs;

- A lack of coordination with other non-military actors, may lead to duplication of efforts;

- Poor quality work, results in short-lived benefits;

- Implementation delays; or

- Inequitable distribution of benefits between or within communities or regions.

- 34

CIMIC tactics, techniques and procedures publication (AM 86-1-1)/TTP8

- 35

Preferably as part of a program.

- 36

The principle of local ownership describes the perception and acceptance of the local population regarding the project.

- 37

During the execution phase CIMIC should control the ongoing process, like costs, local involvement, timings, etc.