III. Non – military actors

3.1. International Organizations

The term international/intergovernmental organizations refers to inter-governmental organizations or organizations whose membership is open to sovereign states. IOs are established by treaties, which provide their legal status. They are subject to international law and are capable of entering into agreements between member states and themselves.

The most prominent IOs are the United Nations (UN) and the European Union (EU). Other examples include the African Union, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and the World Trade Organization. Their missions are highly political by nature.

International Organizations have different mandates and each one of these organizations is complex in terms of organizational structure. UN is an international governmental organization with over 130 agencies. It also comprises humanitarian agencies and agencies that receives their mandate with political agreements. For example, the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) administers and coordinates most development technical assistance provided through the UN system. OCHA is more likely to be involved in coordinating the activities of relief agencies including United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the World Food Program (WFP). The International Organization for Migration (IOM), is another influential organization that may be encountered.

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) are involved in humanitarian peacekeeping and political missions and may therefore operate in similar theatres to NATO. The UN system comprises six principal organs, programmes and funds, specialized independent agencies, departments and offices.

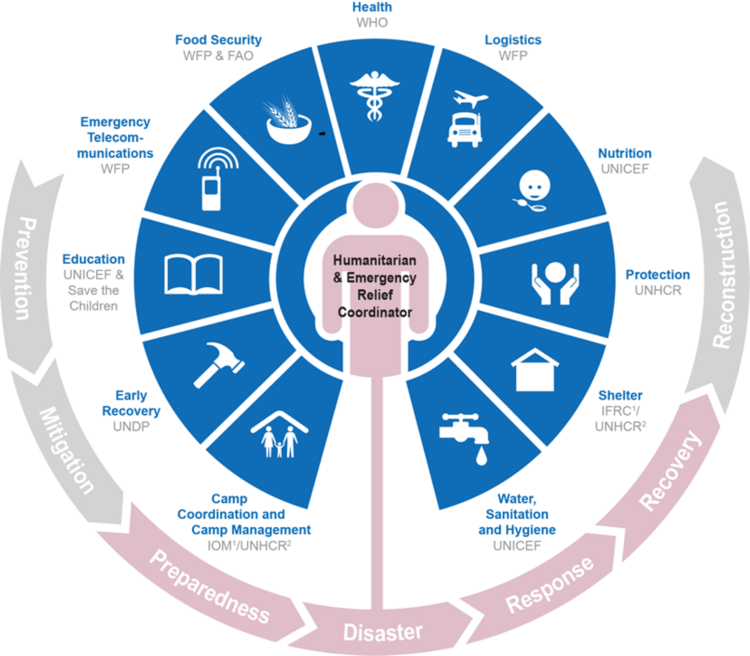

The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) is the part of the United Nations Secretariat responsible for bringing together humanitarian actors to ensure a coherent response to emergencies. OCHA assists governments in mobilizing international assistance when the scale of the disaster exceeds the national capacity. It takes the lead in coordinating humanitarian action, although in response to specific disasters specialized agencies may take on this role depending on the cluster structure and nature of the disaster or conflict.

The United Nations Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination (UN-CMCoord) is the essential dialogue and interaction between civilian and military actors in humanitarian emergencies that is necessary to protect and promote humanitarian principles, avoid competition, minimize inconsistency and, when appropriate, pursue common goals. Basic strategies range from coexistence to cooperation. Coordination is a shared responsibility facilitated by liaison and common training.

Interaction with the humanitarian actors should be made through OCHA, especially in instances where military action may cause humanitarian impact or is required to support humanitarian operations. Activity should be coordinated through established fora or clusters. Where OCHA has established a dedicated UN-CMCoord Officer or focal point function, this is the first point of contact.

United Nations funds, programs and agencies

UN funds, programs and specialized agencies (UN agencies) have their membership, leadership and budget processes separate to those of the UN Secretariat, but are committed to work with and through the established UN coordination mechanisms and report to the UN Member States through their respective governing boards. The UN agencies, most of which also have pre-existing development-focused relationships with Member States, provide sector-specific support and expertise before, during and after a disaster. The main UN agencies with humanitarian mandates include Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), IOM, OCHA, UNDP, United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), UNHCR, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), UN Women, World Food Program (WFP) and World Health Organization (WHO), which support disaster response across needs, from shelter, protection, food security, health, nutrition, education and livelihoods to common services like coordination, logistics and telecommunications.

International Coordination Mechanisms

Effective disaster response requires careful coordination at global, regional and national levels. The UN has established a number of interdependent coordination mechanisms designed to guide relations among humanitarian actors and between humanitarian actors, governments and disaster-affected people to ensure the delivery of coherent and principled assistance.

- At global level; Emergency Relief Coordinator (ERC) is the most senior UN official dealing with humanitarian affairs, mandated by the UN General Assembly to coordinate international humanitarian assistance during emergency response, whether carried out by governmental, intergovernmental organizations or NGOs. The ERC reports directly to the UN Secretary General, with specific responsibility for processing Members States’ requests and coordinating humanitarian assistance; ensuring information management and sharing to support early warning and response; facilitating access to emergency areas; organizing needs assessments, preparing joint appeals, and mobilizing resources to support humanitarian response; and supporting a smooth transition from relief to recovery operations.

- At country Level; UN Resident Coordinator (UN RC) is the designated representative of the UN Secretary General in a particular country and leader of the UN Country Team (UNCT). The UN RC function is usually performed by the UNDP Resident Representative who is accredited by letter from the UN Secretary General to the Head of State or government.

- Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) is appointed by the ERC when large-scale and/or sustained international humanitarian assistance is required in a country. The decision to assign an HC to a country is often made at the start of a crisis and in consultation with the affected government. In some cases, the ERC may choose to designate the UN RC as the HC, in others another Head of Agency (UN and/or international non-governmental organisation (INGO) participating in the coordinated response system) may be appointed and/or a stand-alone HC may be deployed from the pre-selected pool of HC candidates. The HC assumes the leadership of the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) in a crisis. In the absence of an HC, the UN RC is responsible for the strategic and operational coordination of response efforts of UNCT member agencies and other relevant humanitarian actors.

- Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) is an in-country decision making forum focused on providing common strategic and policy guidance on issues related to humanitarian action.

Bridging mechanisms: cluster coordination

Coordination is vital in emergencies. Good coordination means fewer gaps and overlaps in humanitarian organizations’ work and also for other agencies and organizations present in the area of operations, for example the military. It strives for a needs-based, rather than capacity-driven, response. It aims to ensure a coherent and complementary approach, identifying ways to work together for better collective results.

To improve capacity, predictability, accountability, leadership and partnership, the Humanitarian Reform of 2005 introduced new elements to the basis of the international humanitarian coordination system which was set by General Assembly resolution 46/182 in December 1991. The most visible aspect of the reform is the creation of the cluster approach. Clusters are groups of humanitarian organizations (UN and non-UN) working in the main sectors of humanitarian action. They are created when clear humanitarian needs exist within a sector, when there are numerous actors within sectors and when national authorities need coordination support.

Clusters provide a clear point of contact are accountable for adequate and appropriate humanitarian assistance. Clusters create partnerships between international humanitarian actors, national and local authorities, civil society and military (CIMIC).

UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) helps to ensure coordination between clusters at all phases of the response, including needs assessments, joint planning, and monitoring and evaluation.

Please note: Pending the scope of required aid or assistance not every cluster will be established in each operation (UN slogan: tailored to the needs). However each cluster remains under the patronage of a UN-body, although a NGO can take the cluster lead in country due to their expertise.

UN Humanitarian Civil-Military Coordination (UN-CMCoord)

United Nations humanitarian civil-military coordination supports OCHA’s overall efforts in humanitarian operations with a military presence, where OCHA leads the establishment and management of interaction with military actors. This relationship will change depending on the type of emergency and the roles and responsibilities of the military. OCHA supports humanitarian and military actors through training and advocacy on the guidelines that govern the use of foreign military and civil defence assets and humanitarian civil-military interaction. OCHA also seeks to establish a predictable approach to the use of these assets by considering their use during preparedness and contingency-planning activities.

UN-Civil-Military Coordination () is the essential dialogue and interaction between civilian and military actors in humanitarian emergencies that is necessary to protect and promote humanitarian principles, avoid competition, minimize inconsistency and, when appropriate, pursue common goals. Basic strategies range from cooperation to co-existence. Coordination is a shared responsibility facilitated by liaison and common training.

In every humanitarian response, dialogue and interaction with all armed actors is a crucial aspect of humanitarian activities. However, the objectives, strategies and mechanisms will differ. In complex emergencies, humanitarians emphasize the distinction from the military, dialogue and negotiations with non-state armed groups for humanitarian access or protection, as well as security of humanitarian actors. In disasters during peacetime, the focus is likely to be on coordination and appropriate use of foreign military assets (FMA) in support to humanitarian operations.

At all times, the UN-CMCoord Officer has a crucial role to liaise and explain the humanitarian mandate and principles to the military and commanders of other armed actors, and, likewise, in explaining the mandate, rule of engagement and objectives of military and other armed actors to the humanitarian community. This facilitates mutual understanding, working in the same operational environment, and appropriate coordination arrangements.

Four key guidelines have been developed under the auspices of the multi-stakeholder UN-CMCoord Consultative Group and Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), respectively. They set down the principles and concepts for UN-CMCoord; when and how FMA can be considered in support of essential basic needs; how they should be employed; and how UN Agencies and the broader humanitarian community should interact and coordinate with foreign and domestic military forces. They are:

- ‘Oslo Guidelines’ - Guidelines on the Use of Foreign Military and Civil Defence Assets (MCDA) in Disaster Relief - (1994 / Updated Nov. 2006 / Rev. 1.1 Nov. 2007). The Oslo Guidelines were developed to fill the “humanitarian gap” between the disaster needs that the international community is asked to satisfy and the resources available to meet these needs. They address the use of FMA following natural, technological and environmental emergencies in times of peace. They assume a stable government, which remains overall responsible for all relief actions. They also assume that the state receiving FMA provides the necessary security for international organizations.

- ‘MCDA Guidelines’ - Guidelines on the Use of Military and Civil Defence Assets to Support United Nations Humanitarian Activities in Complex Emergencies (March 2003 / Rev. I Jan. 2006). The MCDA Guidelines were developed to cover complex emergencies. They provide guidance on when military and civil defence assets can be used, how they should be employed, and how UN agencies should interface, organize, and coordinate with international military forces. The Guidelines underline that support by military forces is a last resort and must not compromise humanitarian action that FMA should be requested on the basis of humanitarian needs alone, and that FMA support must be unconditional.

- IASC Reference Paper on Civil-Military Relationship in Complex Emergencies (June 2004). It assists humanitarian practitioners in formulating country specific operational guidance on civil-military relations for particularly difficult complex emergencies. Part 1 of the paper reviews, in a generic manner, the nature and character of civil-military relations in complex emergencies; part 2 lists the fundamental humanitarian principles and concepts that must be upheld when coordinating with the military; and part 3 proposes practical considerations for humanitarian workers engaged in civil-military coordination. The Reference Paper is one of the most important guides for the UN-CMCoord Officer to determine appropriate liaison and coordination mechanisms in complex emergencies, and, when relevant, for the development of context-specific guidance.

- IASC Non-Binding Guidelines on the Use of Armed Escorts for Humanitarian Convoys (February 2013 / replaced the IASC discussion paper of September 2001). The Armed Escorts Guidelines underline that as a general rule humanitarian actors will not use armed escorts. There may be exceptional circumstances in which the use of armed escorts is necessary as a last resort to enable humanitarian action. Before deciding on such exceptions, the consequences and possible alternatives to the use of armed escorts must be considered. As a general rule, it is the responsibility of the HCT to collectively assess and agree to their use. Each context has its own specificities, therefore alternatives must derive from a thorough analysis.

Guidelines are non-binding. They are widely accepted reference documents that provide a model legal framework for the development of context-specific or thematic guidance. Topic and context-specific guidance respond to the particular context of humanitarian action.

The type of interaction between humanitarian and military and other armed actors is dictated by the operational environment. The scope and kind of information to be shared, as well as the level of dialogue and coordination, are context-dependent. Generally, in complex emergencies and high security risk environments, the preferred strategy is co-existence. This will ensure distinction between humanitarians and military and other armed actors, and to preserve principled humanitarian action. In disasters in peacetime, closer “cooperation” may be appropriate. CMCoord aims to maximize positive effects of civil-military interaction, while reducing and minimizing negative effects, using the most appropriate strategy and approaches.

Points to take into account

- Militaries can contribute to humanitarian action through their ability to rapidly mobilize and deploy unique assets and expertise in response to specifically identified requirements.

- While military action supports political purposes, humanitarian assistance is based on need and is provided neutrally without taking sides in disputes or political positions on the underlying issues.

- Humanitarians must be aware of the issues emanating from working with the military to ensure that their neutrality, impartiality, operational independence and the civilian character of humanitarian assistance are not compromised.

- Coordination between humanitarians and military forces can range from cooperation to coexistence. OCHA manages the interaction through UN-CMCoord by applying related guidelines.

Effective and consistent humanitarian civil-military coordination is a shared responsibility, crucial to safeguarding humanitarian principles and humanitarian operating space.

European Union

The European (EU) has set up a number of Diplomatic Delegations across the world to promote political and economic reforms. It is also undertaking many operations in specific areas as part of its Common Security and Defence Policy but operates in military conflict in general only, if mandated by United Nations. For example the European Union was mandated by UN in 2014 for a peacekeeping mission in the Central African Republic. The goal of the mission was to stabilize the area after more than a year of internal conflict. The mission ended its mandate after nearly a year in 2015.

- 21

For further information see UN-CMCoord Field Handbook Version 2.0 (2018)